Crisis Management

The topic of Crisis Management addresses the organizational process of making swift or particularly challenging decisions at times of crisis, and how this may differ from regular decision making processes.

A New Perspective

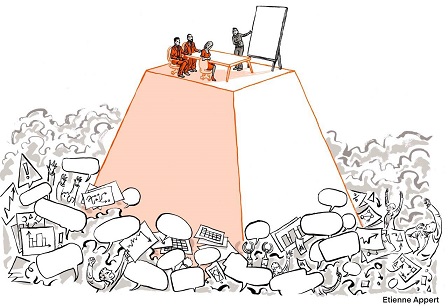

In a Teal organization, everyone is involved in decision making to allow the best response to emerge from collective intelligence. Every historical stage has given birth to a distinct perspective on Crisis Management, and to very different practices:

Red Organizations

In the Red paradigm, the organization's short term planning horizon and its reactive nature makes it familiar with crises. Decisions can be made on a whim and are passed down to employees from above by using the Red breakthrough of command authority.

Amber Organizations

In the Amber paradigm, the organization is more stable and predictable. Processes and procedures define the way things are done. It is assumed that workers need direction. In the unpredictable realm of crisis, the CEO and highest management make decisions which are then translated into orders for those further down the hierarchy. They are expected to follow without question.

Orange Organizations

In the Orange paradigm, decision making is based on effectiveness, measured by impact on measures like profit and market share. Decision-making in Orange is based more on expertise than on hierarchy. In crisis a task force of select advisors might meet confidentially to advise the CEO and board. Top management will be under pressure to regain control and as a consequence decision making may be centralized in the hands of the senior executives . Decisions are typically communicated after they are made and then expected to be implemented swiftly.

Green Organizations

In values-driven, purpose-led Green organizations, decentralization and empowerment help to push day-to-day decision making down to frontline workers who can make them without management approval. For far-reaching decisions, consensus is valued, and sought, by senior management before they act. Crises challenge these practices. For highly contentious and time-sensitive decisions, it may be that the CEO steps in, suspends the consensus model, and makes a top down determination.

Teal Organizations

In the Teal paradigm, everyone is involved in decision making to allow the best response to emerge from collective intelligence. If the advice process needs to be suspended, the scope and time of this suspension are limited.

In Practice

Upholding the advice process

The regular decision making model adopted by Teal organizations is the advice process, which distributes decision-making. This remains the preferred approach to deal with crisis situations.

Trusting the process

Crisis Management via the advice process is an ultimate demonstration of [Self-Management Self Management]. In crises, sensitive and urgent decisions may have negative implications for employees and the organization as a whole: for example, loss of jobs, or selling off parts of the business.

It is natural, given the earlier organization models, to question the capacity of staff to be included in making decisions in such sensitive circumstances.

A leader of a Teal organization is challenged to trust in the advice process anyway. They risk the unknown reaction of the employees, and the potential for things to descend into chaos or adversarial exchanges. However, when the advice process is not used, there is a risk of losing the trust of the employees by doubting their ability to resolve the situation. When employees are fully engaged with the advice process in a crisis, they are asked to share responsibility for difficult decisions and trusted to make a contribution. This is empowering and helps the organization to grow.

Suspending the advice process

Occasionally a crisis may require the advice process to be suspended because of the scale or urgency of the situation. Under these circumstances the leader may choose to suspend the advice process temporarily. This can be acceptable providing:

- the reasons for the suspension are fully disclosed

- the limitations (time period, areas of decision making etc) are explained

- Decision making is passed to a capable person rather than the leader

See AES below.

Self-management

Dealing with a crisis via the advice process is a key test of self management. Leaders are asked to suspend any desire to take charge and trust the workforce to deliver effective solutions. There is an underlying belief that employees are responsible, committed and capable.

Wholeness

By upholding the advice process, even in crisis situations, leader(s) are forced to face a fear that losing control could imperil the organization, cause chaos, and risk the interests of stakeholders. Crisis situations provide an opportunity for leaders to demonstrate their wholeness by being transparent, potentially vulnerable and genuinely supportive of their colleagues' participation. Employees in turn are invited to take responsibility for their own feelings in situations that may have unwelcome outcomes.

A crisis situation offers an opportunity for an organization to come together as a whole to find solutions. This often leads to more powerful solutions than those created by a leader or a group of advisors in isolation. When these situations are successfully addressed, the organization collectively experiences a growth into [Wholeness wholeness].

Evolutionary purpose

When employees are engaged in the advice process in a crisis, they are invited to understand what is unfolding and participate actively in the decisions that need to be taken. Deciding what to do asks everyone to re-connect with the purpose of the organization. Serving the needs of the evolutionary purpose becomes an important factor in deciding what to do. Without this reference point, decision making can easily be dominated by self interest and survival needs.

Frequently Asked Questions

'The buck stops here' is part of our inheritance of 'heroic management'. Theoretically, it sounds unarguable. Perhaps the best answers are what can happen in practice. Three examples of crisis management below (Favi, Buurtzorg, AES) show how three Teal organizations have handled crises constructively.

Concrete cases for inspiration

AES suspends the advice process as gracefully as possible

In fall of 2001, after the terrorist attacks and the collapse of Enron, AES’s stock price plummeted. The company needed access to capital markets to serve its high debt levels but found them suddenly closed. Swift and drastic action was needed to prevent bankruptcy. A critical question was: how many and which power plants would need to be sold off to raise the necessary cash? With 40,000 people spread around the world, Dennis Bakke, the CEO, could hardly convene everybody and stand on a soapbox like Zobrist at FAVI. And the problem was so complex that he couldn’t simply send out a blog post with two alternatives, like Jos de Blok did at Buurtzorg.

Bakke chose a course of action that temporarily suspended the advice process in a way that nevertheless minimized the risk of under-mining trust in self-management. He didn’t work out a plan behind closed doors with his management team; instead, he publicly announced that top-down decision-making would be made during a limited time for a limited number of decisions, albeit critical ones. The advice process would remain in force for all other decisions. To investigate the best course of action and make the tough calls, Bakke appointed Bill Luraschi, a young and brilliant general counsel. Luraschi wasn’t regarded as one of the most senior leaders nor as someone who would seek a leading role in the future. The signal was clear: the senior leaders of the organization were not looking to exert more power. Top-down decision-making would be handled by someone with no thirst for power, and it really would be temporary.

If the advice process needs to be suspended in times of crisis, these two guidelines can serve to maintain trust in self-management: give full transparency about the scope and timeframe of top-down decision-making, and appoint someone to make those decisions who will not be suspected of continuing to exert such powers when the crisis is over.

Joe de Blok averted a cash crunch by asking his nurses to work harder

Buurtzorg faced a crisis in 2010 and mastered it using the advice process. The young company was growing at breakneck speed when Jos de Blok heard that health insurance companies had threatened to withhold €4 million in payments to Buurtzorg, citing technical reasons (the more likely reason: the insurance companies wanted to signal to Buurtzorg that it was growing too fast at the expense of established providers). A cash crunch loomed. Jos de Blok wrote an internal blog post to the nurses exposing the problem. He put forward two solutions: either Buurtzorg could temporarily stop growing (new teams cost money at first) or nurses could commit to increasing productivity (increasing client work within the contract hours). In the blog comments, nurses overwhelmingly chose to work harder because they didn’t like the alternative: slower growth would have meant saying no to clients and nurses wanting to join Buurtzorg. In a matter of a day or two, a solution to the cash problem was found (and after some time, the insurance companies eventually disbursed the withheld funds).

CEO of FAVI, Jean-Francois Zobrist asks everyone on the shop floor for help in the wake of the first Gulf War.

It was a common occurrence, that when faced with difficult and critical decisions at FAVI, Zobrist would readily admit he needed help to find a good answer. On impulse, he would go around the shop floor and ask everyone to stop machines, and he would climb on a soapbox and share the problem with all the employees, trying to figure the course of action. The first major crisis under his leadership occurred in 1990 when car orders plummeted in the wake of the first Gulf War. Stocks were piling up, and there simply wasn't enough work to keep workers busy. Capacity and costs needed to be reduced.

There was one obvious solution: fire the temp workers. But at FAVI, no one was really considered a temp worker. For reasons related to labor laws in France, new recruits were hired as temp workers for 18 months before they were offered a full contract. Most of them were already considered full members of their teams. By firing the temps, FAVI would rescind its moral commitment to them, and it would lose talent it had invested in, with a recovery perhaps only a few months away. With many questions and no clear answers, Zobrist found himself on the soapbox and shared his dilemma with all employees in that shift (including the temp workers whose fate was being discussed). People in the audience shouted questions and proposals. One worker said, "This month, why don't we all work only three weeks and get three weeks' pay, and we keep the temp workers? If we need to we will do the same thing next month as well." Heads nodded, and the proposal was put to a vote.

To Zobrist's surprise, there was unanimous agreement. Workers had just agreed to a temporary 25 percent salary cut. In less than an hour, the problem was solved and machine noise reverberated around the factory again. Zobrist’s ability to keep his fear in check paved the way for a radically more productive and empowering approach and showed that it is possible to confront employees with a harsh problem and let them self-organize their way out of it.

AES suspends the advice process as gracefully as possible

In fall of 2001, after the terrorist attacks and the collapse of Enron, AES’s stock price plummeted. The company needed access to capital markets to serve its high debt levels but found them suddenly closed. Swift and drastic action was needed to prevent bankruptcy. A critical question was: how many and which power plants would need to be sold off to raise the necessary cash? With 40,000 people spread around the world, Dennis Bakke, the CEO, could hardly convene everybody and stand on a soapbox like Zobrist at FAVI. And the problem was so complex that he couldn’t simply send out a blog post with two alternatives, like Jos de Blok did at Buurtzorg.

Bakke chose a course of action that temporarily suspended the advice process in a way that nevertheless minimized the risk of under-mining trust in self-management. He didn’t work out a plan behind closed doors with his management team; instead, he publicly announced that top-down decision-making would be made during a limited time for a limited number of decisions, albeit critical ones. The advice process would remain in force for all other decisions. To investigate the best course of action and make the tough calls, Bakke appointed Bill Luraschi, a young and brilliant general counsel. Luraschi wasn’t regarded as one of the most senior leaders nor as someone who would seek a leading role in the future. The signal was clear: the senior leaders of the organization were not looking to exert more power. Top-down decision-making would be handled by someone with no thirst for power, and it really would be temporary.

If the advice process needs to be suspended in times of crisis, these two guidelines can serve to maintain trust in self-management: give full transparency about the scope and timeframe of top-down decision-making, and appoint someone to make those decisions who will not be suspected of continuing to exert such powers when the crisis is over.