Organizational Structure

This article discusses the structures through which people coordinate work and distribute power in Teal organizations.

A New Perspective

All organizations prior to Teal were structured as pyramids for a simple reason: it is a natural consequence of the boss-subordinate relationship. In self-managed organizations, peer commitments replace the boss-subordinate relationship, and the pyramid disappears. Authority is distributed, and work is conducted by decentralized, self-managing teams or networks. The static hierarchy of the pyramid gives way to fluid natural hierarchies, where influence flows to people who have the most expertise, passion or interest. Freed from the rigidity and sluggishness of a command and control structure, Teal organizations can be more responsive and more energized. They are “emergent”: the behavior of the organization ‘emerges’ from the actions of teams and individuals.[1]

The following describes organizational structure in earlier stages:

Red organizations

In the Red paradigm, organizations are structured around a strong leader who, largely through fear, exercises power over others. There is little formal hierarchy, and Red organizations rely largely on the chief’s ability to keep all its members in line, rather like wolves in a pack around the alpha male.

Amber organizations

In the Amber paradigm,the organization chart with reporting lines appears, resulting in a hierarchical pyramid and a clear chain of command. People identify with job titles and their place in the hierarchy. Decisions are made at upper levels of the hierarchy while lower levels follow orders.

Orange organizations

In Orange organizations, the pyramid remains the fundamental structure, although some additional freedom is given. Project groups, virtual teams, cross-functional initiatives, expert staff functions, and internal consultants are created to drill holes into rigid functional and hierarchical boundaries in order to speed up communication and foster innovation.

Green organizations

Green organizations typically still operate with the pyramid structure, but there is more empowerment of front-line employees. Higher managers are asked to share control: to move from being doers, problem solvers and fixers to being “servant leaders”. This is often symbolized by an "inverted pyramid", where the CEO at the bottom supports senior and middle managers who in turn support front-line employees.

In Practice

Although the pyramid disappears in Teal, it would be a mistake to think that self-managing organizations are simply flat and structureless. Teal organizations to date seem to fall into three broad types of structure to fit the context in which they operate. These are described further below. However all share the common attributes of distributed authority and natural hierarchies.

Distributed authority

In traditional organizations, when power is concentrated at the top, bosses can approve or invalidate a decision made by a subordinate. In Teal organizations, power is distributed There are no bosses, only coaches. Anyone who senses a problem or an opportunity can initiate a decision making process, using methods that leverage the collective intelligence of the organization.

In traditional hierarchies, power is concentrated at the top, and can be exercised in a top-down fashion: bosses can approve or invalidate a decision made by a subordinate. In Teal organizations, power is distributed: everyone who senses a problem or an opportunity can step up and initiate a decision making process, using methods that leverage the collective intelligence of the organization about the topic at hand. These methods —sometimes called "advice process"— don't involve, as a common misconception about self-managing structures, consensus decision making.

Natural hierarchies

A common misconception about self-management is that everyone is "equal" and should have equal say in decisions. In reality, when traditional hierarchies are gone, lots of natural and fluid hierarchies blossom―hierarchies of development, skill, talent, expertise, and recognition. On every issue, some colleagues will have more expertise than others, more passion, or more willingness to help. Decision rights and influence flow to those who have the expertise or willingness to contribute. Fluid, natural hierarchies replace the fixed power layers of the pyramid. A person’s influence depends on her talent, interest, skills, and the confidence of her colleagues. It is no longer determined by her position in the organization chart.

Archetypes of structure

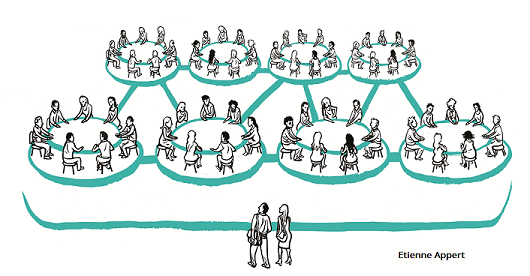

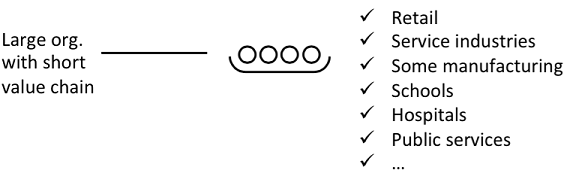

Self-managing organizations adopt different forms to fit the context in which they operate. There seem to be three broad types of self-managing structures that have emerged so far:

- Parallel teams

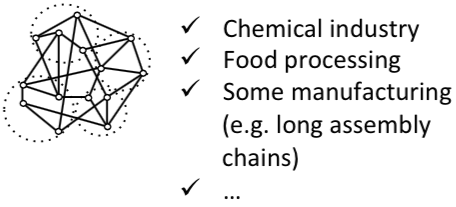

- Web of individual contracting

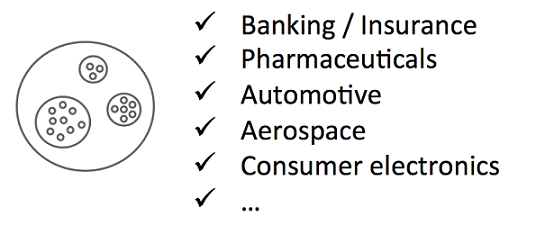

- Nested circles

These structures are not mutually exclusive, and some organizations exhibit a mixture of these types.

This is the most common structure found to date in Teal organizations.[2]Examples would include Buurtzorg (geographic teams) and FAVI (client teams) (see “Concrete examples for inspiration” below). This model is highly suitable when work can be broken down in ways that teams have a high degree of autonomy, without too much need for coordination across teams. They can then work side by side. In this model, it is within the team that colleagues define their roles and the mutual commitments they make to each other. Teams also typically handle their own recruitment, planning, establish their investment needs, devise a budget (if a budget is needed), track their financial and non-financial results, and so on.

In an ideal situation, each team is fully autonomous and performing all tasks from start to finish. When that is the case, every single person in the organization has the satisfaction of seeing the entire organization’s purpose come to life, and not just a small slice of it as is often the case in large specialized organizations. In practice, there will often be a need for some people or teams who take on coordinating or supporting roles with a more narrow focus:

- Team coaches: In Teal Organizations, there are no middle managers. But teams often feel a need to be supported by someone external that can help them work through problems. At Buurtzorg, they are called regional coaches; at RHD, hub leaders.

- Supporting teams: For some tasks, duplication in every team doesn’t make sense. At FAVI, for example, the great majority of teams are client facing―the Audi team, the Volkswagen team, etc. However, a few teams support other teams, such as the foundry team. It would not be practical for the teams to operate the foundry in turns, nor would it make sense to duplicate the equipment and have a foundry within each team. RHD has units responsible for areas such as training (its “miniversity”), real estate, and payroll, that support all the units in the field.

- Supporting roles: The self-management model pushes expertise down to the teams, rather than up into staff functions. But for certain specific expertise or for coordination purposes, creating a supporting role can make sense. At FAVI, for instance, there is an engineer who helps teams exchange innovations and best practices.

Web of individual contracting

Individual contracting, as has been pioneered by Morning Star, a California-based tomato processing company, is a natural fit for continuous and relatively stable processes, such as can be found in the chemical industry, in food processing, or in long assembly chains. Each major step in the process often involves only a few people, and so a nested structure is not needed. Through individual one-on-one contracting, colleagues can make clear agreements with their upstream and downstream counterparts and anyone else they work closely with. These commitments are often formalized in a written document.

Investment budgets and financial results, on the other hand, are set up and discussed in teams, just as in the model of parallel teams. (Morning Star calls them “Business Units,” and each Business Unit is linked to a particular step in the process―say, tomato preparation, dicing, canning, or packaging―or to a support service―for instance, steam generation or IT.)

Nested teams (Circles)

Some industries have not only long, but also deep value chains, when certain steps in the value chain involve both a large number of people and complex tasks (for instance, research in a pharmaceutical company or marketing in a large retail bank). Consumer electronics firms, large media companies, banks, insurance companies, car manufacturers, aerospace companies, and airline companies are likely to have long and deep value chains. For these types of companies, nested teams (often called circles) might be particularly appropriate, as they allow an overall purpose to be broken down into successively less complex and more manageable pieces.

This structure was formalized by Kees Boeke in the mid 20th century in a system called Sociocracy (first applied in a school in the Netherlands). Holacracy, an organizational system pioneered by Brian Robertson in his software company Ternary Software, is also structured in concentric circles (see “Concrete examples for inspiration” below).

Through nesting, circles gradually integrate related activities, so there is a hierarchy of purpose, complexity, and scope, but not of people or power. Each circle has full authority to make decisions within the scope of its specific purpose. Decisions are not sent upwards, and cannot be overturned by members of overarching circles.

Frequently Asked Questions

Self-management

Teal organizational structures are driven by self-management. The traditional boss-subordinate relationship gives way to a decentralized team structure and peer to peer commitments.

Wholeness

Pyramidal structures are built on the (often unconscious) assumption that people cannot be trusted and must be controlled by their hierarchical superior. In Teal organizational structures, people are freed from the constraints of authority and can thus show up more fully.

Evolutionary purpose

In Teal organizations, people’s actions are guided by their sense of the organization’s evolutionary purpose, not by what they are being told to do by someone higher up the organizational chain. Self-managing systems, based on sense and respond as opposed to command and control, tend to evolve much faster and respond more quickly to changes in the environment. Pyramidal organizations tend to change through less frequent, less timely and more brutal re-organizations.

In today’s world, the predominant, default organizational model is that of the pyramid, with an executive committee, middle managers, staff functions, and policies and procedures to ensure control. Self-managing systems are still the exception, and many people's default behaviors, even in established self-managing organizations, can revert to those of more traditional, hierarchical management. This might explain why in all self-managing organizations to date, the founder or the most senior “leader” has filled one particular role: that of "holding the space" of distributed authority. Whenever people in the organization, consciously or unconsciously, revert to traditional management control mechanisms, the leader reminds everyone about the fundamental assumptions and encourages them to find solutions in line with the self-managing nature of the organization.

In self-managed teams, many management tasks disappear, since people are no longer being “managed”. Other tasks (planning, setting objectives, monitoring team performance, recruiting, etc.) remain, and it is up to the team to make it clear among themselves what the various roles and task responsibilities of the team members are. In some cases, such tasks can simply be spread among team members (I do the planning, you lead the recruiting, etc.). Such a model works well when the nature of the team’s operational roles allows for flexibility (e.g., knowledge workers who can interrupt their primary work or nurses who can take time between patient visits for administrative tasks). Other types of work require fixed and dedicated hours that cannot be easily interrupted. Teachers, for instance, can't easily leave the classroom and machine operators can't easily leave their workplace. In such cases, it might be necessary to have a team coordinator that isn't tied to a classroom or a machine to take on a number of the management tasks.

Having a team coordinator nevertheless carries a risk. Our cultural baggage of hierarchy is so strong that over time, team coordinators could start behaving like bosses and become the primary decision makers on their teams. At FAVI, a simple but powerful relief valve exists. Should a team leader find the taste of power too sweet, workers can choose at any moment to join another team.

See also, “Role Definition and Allocation”.

Concrete cases for inspiration

Fitzii is organized in three parallel teams and uses a Venn diagram to illustrate where teams overlap and share decision making

Fitzii is organized in three parallel teams along functional lines – product & development, sales & marketing, and hiring success. Each has a senior person who plays a strategy and planning role but has no authority over other team members (Fitzii uses the advice process and other peer-based processes for decision making).

Fitzii maintains a Venn diagram to show the relationship between its three teams. Each team is responsible for its own plans; every combination of two teams has shared plans where their work overlaps; and finally, certain topics rest in the center of the Venn where any changes require input from all three teams. “Center of the Venn” topics include Fitzii’s evolutionary purpose, strategy and thematic goals, product and service changes that could significantly affect customers, and people and culture practices such as self-management.

A nested team structure

Holacracy is an organizational operating system adopted by hundreds of organizations around the world using a nested team structure. It refers to teams as “circles” and to the structure as a whole as a “holarchy” (as distinct from a hierarchy). In a holarchy, each circle is not subjugated to those above it, but retains autonomy, individual authority, and wholeness. Circles are grouped within broader circles, all the way up until the biggest circle contains the entire organization. This circle is called the “Anchor Circle”. Teams near the "top" work on wider purposes; teams near the "bottom" work on more specialized purposes. Every circle and role within the holarchy retains real autonomy and authority as a cohesive, whole entity itself, while also having real responsibilities as a part of a larger entity. For a fuller description, see Holacracy's website.

Buurtzorg uses a geographically-based parallel team structure and team coaches.

At Buurtzorg, a Dutch neighbourhood nursing organization, nurses work in teams of 10 to 12, with each team serving around 50 patients in a small, well-defined neighbourhood. The team is in charge of all tasks that were previously fragmented across different departments.

Each team has a coach. The coach has no decision-making power and works with 40 to 50 teams at a time, making sure that no one team becomes overly dependent on the coach. The coach's role is to ask insightful questions that help teams find their own solutions.

The team is responsible for doing the intake, planning, vacation scheduling as well as administration. They even decide where to rent an office and how to decorate it. There is no leader within the team; important decisions are made collectively.

Because of this, a problem-solving culture thrives. Nurses can't offload difficult decisions to a boss and when things get tense, stressful, or unpleasant, there is no boss and no structure to blame The team knows they have all the power and latitude to solve their own problems.

The teams of nurses aren't simply empowered by their hierarchy. They are truly powerful because there is no hierarchy that has decision-making power over them. Each team is also responsible for their own recruitment. Because the team members make hiring decisions themselves, they are emotionally invested in making the recruit successful.

The absence of rules and procedures imposed by headquarters staff functions creates a huge sense of freedom and responsibility throughout the organization.

The results achieved by Buurtzorg speak for themselves. A 2009 Ernst & Young study found that Buurtzorg requires, on average, close to 40 percent fewer hours of care per client than other nursing organizations. This is despite the fact that nurses in Buurtzorg take time for coffee and talk with patients, their families, and neighbors, while other nursing organizations have come to tightly allocate the time allowed for almost every service. . At Buurtzorg, patients stay in care only half as long, heal faster, and become more autonomous.

FAVI employs a customer-based parallel team structure with supporting teams

FAVI’s factory has more than 500 employees that are organized in 21 teams called “mini-factories” of 15 to 35 people. Most of the teams are dedicated to a specific customer or customer type (the Volkswagen team, the Audi team, the Volvo team, and so forth). There are a few upstream production teams (the foundry team, the mold repair team, maintenance), and support teams (engineering, quality, lab, administration, and sales support). Each team self-organizes; there is no middle management, and there are virtually no rules or procedures other than those that the teams decide upon themselves. The staff functions have nearly all disappeared. The former HR, planning, scheduling, engineering, production-IT and purchasing departments have all been shut down. Their tasks have been taken over by the operators in the teams, who do their own hiring, purchasing, planning, and scheduling. The sales department has been disbanded too. The sales account manager for Audi is now part of the Audi team, just as the sales account manager for Volvo is part of the Volvo team. There is no head of sales above the group of account managers. In the old structure, white-collar workers in offices with windows overlooking the shop floor planned in detail what the workers needed to do, by when, and how. Now blue-collar workers effectively wear their own white collars and no longer receive instructions from above.[3]

A lattice organization

You can’t say there is no hierarchy at Happy, as there are two clear leaders: Henry Stewart, founder and Chief Happiness Officer, and Cathy Busani, Managing Director. However there isn’t a rigid structure.

There are three departments: Happy Computers (IT Training), Happy People (leadership and personal development) and apprenticeships (funded in the UK by an Apprenticeship levy that every organisation has to pay).

Each department does have a Head but it is not necessarily a relationship between them and the people in those departments. Each person chooses who they would like to be their “M&M”. The title M&M was chosen by the staff and means Multiplier and Mentor - although the role is more of a coach.

Where staff work in a team, there is a team job description, rather than individual ones. That means that people can choose which roles in the team they want to play and these often shift.

There is a regular staff meeting (fortnightly before the pandemic, weekly during it). This will decide anything that affects everybody.

There is also a monthly Joyful meeting. This includes Henry, the heads of department and people elected by the staff as “potential leaders”. Anybody can attend this meeting. Wherever possible the teams make their own decisions, without referring to the head of that department.

Happy’s organisation chart is a series of circles with the picture of the person inside. It includes:

- Job title

- When they work

- Whether they are an activist, pragmatist, reflector or theorist (Honey and Mumford)

- Their 5 key strengths based on Strengthfinder (R)

The colours show their communication style, when at ease (external circle) and when under pressure (internal circle)

- Red = Driver,

- Yellow = Expressive,

- Green = Amiable,

- Blue = Analytical

The arrows indicate who coaches who. The chart is the work of two front-line staff who were pre-approved to come up with it.

A sociocratic framework, with Teal principles

Reddico’s structure uses the principles of Teal, with a formalized model taking the shape of a typical sociocratic framework.

All departments and teams are self-managed – each group then decides how it will operate (how often meetings will be, how information will be shared, who will be part of that group etc.). Information from team meetings is distributed to the whole company (radical transparency), with the majority of the team working on the current 90-days.

Each team also elects a representative for wider circle discussions (for instance, Operations). Information is then able to flow throughout the organization.

https://reddico.co.uk/uploads/2021/07/org-structure---july-2021-jpeg-2.jpg

Related Topics

Notes and references

Teal organizations can be thought of as an example of a “complex adaptive system”: a "complex macroscopic collection" of relatively "similar and partially connected micro-structures" formed in order to adapt to the changing environment and increase its survivability as a macro-structure. They are complex in that they are dynamic networks of interactions, and their relationships are not aggregations of the individual static entities. They are adaptive in that the individual and collective behaviors mutate and self-organize corresponding to the change-initiating micro-event or collection of events." Source: Complex Adaptive Systems, Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Complex_adaptive_system ↩︎

Laloux, Frederic. Reinventing Organizations. Nelson Parker (2014), page 319. ↩︎

Laloux, Frederic (2014-02-09). Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness (Kindle Locations 1704-1715). Nelson Parker. Kindle Edition. ↩︎