Decision Making

The topic of decision-making discusses how decisions are made within organizations, and by whom. In Teal organizations, decision-making authority is truly distributed throughout the organization.

A New Perspective

In Teal organizations decision-making is highly distributed. Front-line individuals or teams have the opportunity to make decisions that affect their work. While these decisions may not need to be validated by a hierarchy or consensus, it is expected that experts, and those affected, should be involved.

Every historical stage has given birth to a distinct perspective on decision making and to very different practices. In earlier periods, decisions may have been made at the top. Today, some organizations consciously try to "empower" people at the bottom.

Red organizations

In the Red paradigm, decisions of any consequence are made by the boss/chief. Employees must seek his or her approval, or risk severe consequences. Red organizations can be efficient, but control, exercised through fear, limits the willingness of members to make independent decisions.

Amber organizations

In the Amber paradigm, decision-making authority is determined by an individual’s status in the hierarchy. Innovation is not particularly valued; following standard operating procedures is. A clear chain of command supported by formal processes defines who can do what. Individuals are expected to embrace these processes and traditions.

Orange organizations

In the Orange paradigm, organizations are viewed as machines that need to be 'tuned' for efficiency. Top management announces the overall direction or strategy and then objectives cascade down. Managers draw up plans for approval based on their objectives. These plans guide decision-making toward the achievement of goals—for example, profit and market share. Team members are invited to suggest initiatives and participate in the decision-making process. This encourages innovation and debate. The overriding aims are predictability and control.

Green organizations

Values-driven, purpose-led Green organizations strive to serve multiple stakeholders. Front-line employees, for example, are often encouraged to make significant decisions without higher approvals in the interests of serving customers and the wider stakeholder community. They are in touch with the day-to-day issues, and trusted to devise better solutions than ‘experts’ who may be far away. Emphasis is on maintaining a strong, often “familial”, culture. Consensus is highly valued.

Teal organizations

In Evolutionary-Teal, there is a shift from external to internal yardsticks in decision-making. People are now concerned with the question of inner rightness: does this decision seem right? Am I being true to myself? Is this in line with who I sense I am? Am I being of service to the world? With fewer ego-fears, people are able to make decisions that might seem risky. All the possible outcomes may not have been weighed up, but the decision resonates with deep inner convictions. People develop a sensitivity for situations that don’t quite feel right, and situations that demand that they speak up and take action, even in the face of opposition or with seemingly low odds of success. This is born out of a sense of integrity and authenticity.

In Practice

The advice process

Almost all Teal organizations use, in one form or another, what an early practitioner (AES) called the “advice process.”

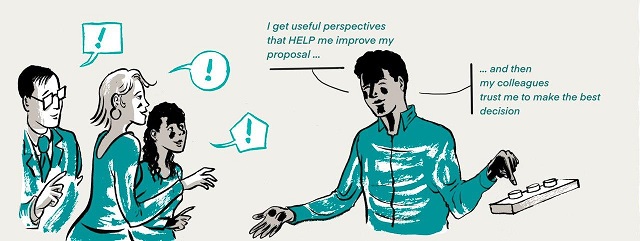

It comes in many forms, but the essence is consistent: any person can make any decision after seeking advice from 1) everyone who will be meaningfully affected, and 2) people with expertise in the matter.

Advice received must be taken into consideration. The point is not to create a watered-down compromise that accommodates everybody’s wishes. It is about accessing collective wisdom in pursuit of a sound decision. With all the advice and perspectives the decision maker has received, they choose what they believe to be the best course of action.

Advice is simply advice. No colleague, whatever their importance, can tell a decision-maker what to decide. Usually, the decision-maker is the person who first noticed the issue, or the person most affected by it.

In practice, this process proves remarkably effective. It allows anybody to seize the initiative. Power is no longer a zero-sum game. Everyone is powerful via the advice process.

It's not consensus

We often imagine decisions can be made in only two ways: either by the person with authority (someone calls the shots; some people might be frustrated; but at least things get done), or by unanimous agreement (everyone gets a say, but it can be frustratingly slow).

It is a misunderstanding that self-management decisions are made by getting everyone to agree, or even involving everyone in the decision. The advice seeker must take all relevant advice into consideration, but can still make the decision.

Consensus may sound appealing, but it's not always most effective to give everybody veto power. In the advice process, power and responsibility rest with the decision-maker. Ergo, there is no power to block.

Ownership of the issue stays clearly with one person: the decision maker. Convinced she made the best possible decision, she can see things through with enthusiasm, and she can accept responsibility for any mistakes.

The advice process, then, transcends both top-down and consensus-based decision making.

Benefits of the advice process

The advice process allows self-management to flourish. Dennis Bakke, who introduced the practice at AES (and who wrote two books about it), highlights some important benefits: creating community, humility, learning, better decisions, and fun.

- Community: it draws people, whose advice is sought into the question at hand. They learn about the issue. The sharing of information reinforces the feeling of community. The person whose advice is sought feels honored and needed.

- Humility: asking for advice is an act of humility, which is one of the most important characteristics of a fun workplace. The act alone says, "I need you“. The decision maker and the adviser are pushed into a closer relationship. This makes it nearly impossible for the decision-maker to ignore the advice.

- Learning: making decisions is on-the-job education. Advice comes from people who have an understanding of the situation and care about the outcome. No other form of education or training can match this real-time experience.

- Better decisions: chances of reaching the best decision are greater than under conventional top-down approaches. The decision maker has the advantage of being closer to the issue and has to live with responsibility for the consequences of the decision. Advice provides diverse input, uncovering important issues and new perspectives.

- Fun: the process is just plain fun for the decision-maker, because it mirrors the joy found in playing team sports. The advice process stimulates initiative and creativity, which are enhanced by the wisdom from knowledgeable people elsewhere in the organization.

Steps in the advice process

There are a number of steps in the advice process:

- Someone notices a problem or opportunity and takes the initiative, or alerts someone better placed to do so.

- Prior to a proposal, the decision-maker may seek input to sound out perspectives before proposing action.

- The initiator makes a proposal and seeks advice from those affected or those with expertise.

- Taking this advice into account, the decision-maker decides on an action and informs those who have given advice.

Forms the advice process can take

Because the advice process involves taking advice from those affected by a decision, it naturally follows that the bigger the decision, the wider the net needs to be cast - including, if these roles exist, the CEO or board.

For minor decisions, there may be no need to seek advice. For larger decisions, advice can come through various channels, including one-on-one conversations, meetings, or online communication.

Some organizations have specific types of meetings to support the advice process, or follow formal methods. (See Buurtzorg and Holacracy below). Some organizations choose to have circles made up of representative colleagues who go through the advice process on behalf of the whole organization.

When decisions affect large numbers, or people who cannot meet physically, the process can happen via the internet.

- The decision-maker can post a proposal on the company blog and call for comments or invite email responses and then process the advice they receive.

- The organization can use decision-making software like Loomio, a free and open-source tool. The process for using the advice process on Loomio: start a discussion to frame the topic and gather input, host a proposal so everyone affected by the issue can voice their position, and then the final decision-maker specifies the outcome (automatically notifying the whole group).

Equal Experts, a network of software consultants based in the UK, specialising in agile delivery, has written an open playbook to share their ongoing experience of a real-world implementation of the Advice Process (the organization has approximately 1100 members in 2021). This book is available at https://advice-process.playbook.ee.

Underlying mindsets and training

The advice process is a tool that helps decision-making via collective intelligence. Much depends on the spirit in which people approach it. When the advice process is introduced, it might be worthwhile to train colleagues not only in the mechanics but also on the mindset underlying effective use.

The advice process can proceed in several ways, depending on the mindset people bring to it:

- The initiator can approach it authoritatively ("I don't care about what others have said" or, alternatively, "I fully comply with what others - someone highly respected, or the majority - have said").

- They can approach from a perspective of negotiation or compromise ("I'll do some of what they say so they're happy, but it will increment my frustration account by 1").

- They can approach it co-creatively, which is the spirit of the advice process ("I will listen to others, understand the real need in what they say, and think creatively about an elegant solution").

Role modeling

When the advice process is first introduced, the founder and/or CEO need to be role-models. Power is initially held by organizational leaders, and it doesn't get distributed by magic - successfully distributing leadership requires careful, proactive effort. By role modeling, others will take cues from their behavior.

Role modeling can take several forms:

- When you want to make a decision, pause and ask: Am I the best person for this decision? (That is, the person most closely linked to the decision, or the person with most energy, skill, and experience to make it?). If not, ask the person you think is better placed to take the initiative. If he/she doesn't want to, you might be best placed after all.

- If you are the right person to make a decision, identify those from whom you should seek advice. Approach them and explain what you are doing. ("I'm playing by the advice process. Here is an opportunity I see. This is the decision I propose to take. Can you give me your advice?"). You can also share who else you are asking for advice. Once you've received advice and made your decision, inform those you consulted (and anyone else who should know).

- When colleagues ask you to make a decision ("What should I do?"), instead ask them "What is your proposed decision?". In the same vein, state clearly that you no longer give approval for decisions. Instead, share your advice and suggest who else to ask. Remind them the decision is theirs.

For many leaders, unlearning the habit of making all the decisions is hard. It requires commitment and mindfulness. If you find yourself falling into the old pattern, take the opportunity to acknowledge your mistake, and restate the importance of the process. This can turn a mistake into a powerful learning moment. Better habits are formed through repeated practice.

Consent-based decision making

A variation of the advice process is consent-based decision making. "Consent" is different from "consensus" in the sense of unanimity. The consent principle says that a decision can be made as long as no one has a reasoned, substantial objection (also known as a "block"). Consent doesn't mean everyone loves the decision, but that they can live with it.

In practice, consent means that if one person raises a principled objection, the decision is blocked. The proposer must pause and, together with the objector, devise a solution that overcomes the objection. A block in a consensus process is a signal to the whole team to "swarm" to understand the objection and problem solve.

Giving such power to a principled objection can be both valuable and dangerous. Valuable because sometimes a single person senses something important that no one else sees. On the other hand, such power can be abused if people block decisions for reasons other than purpose. Groups that use consent-based decision-making often take blocking and shared understanding about policies and culture around blocking very seriously for this reason. (For a real-world example, see the Enspiral Decision Agreement).

Some methods, like Holacracy, deem an objection valid only if the argument passes stringent tests, such as it makes matters worse. A colleague cannot block a proposal simply because he or she thinks they have a better proposal, or because they don't love an idea.

(for a description of Consent Based Decision, see https://thedecider.app/consent-decision-making)

The advice process within a hierarchy

Some organizations want to move toward self-management, but cannot move away from hierarchy completely. Others, especially large organizations, prefer to adopt interim steps. This can be part of a transition to self-management.

AES, the 40,000 employee company where the term "advice process' was coined, operated with remnants of a hierarchy. Anyone could initiate the process, but it was mandatory to consult certain categories of colleagues. These might include one's superiors, or even the board.

Sources that inform decision-making

Teal organizations tend to take a broad range of sources into account:

- Rationality: Many think that rationality rules, and is the legitimate basis for decision-making. Teal considers rational, analytical approaches to be critical, but not the only source to inform decision making.

- Emotions: Whereas the modern-scientific perspective is wary of emotions, Teal recognizes that wisdom is to be found there when we learn to inquire into their significance: "Why am I angry, fearful, ambitious, or excited? What does this reveal about me or about the situation that is unfolding?"

- Intuition: Wisdom can be found in intuition, too. Intuition honors the ambiguous, paradoxical, non-linear nature of reality. We unconsciously connect patterns in ways that our rational mind cannot. Many great minds, like Einstein, had a deep reverence for intuition. They claim it is a muscle that can be trained. Learning to pay attention to intuitions, to question them for guidance, allows intuitive answers to surface.

- Paradoxical thinking: A Teal breakthrough is the ability to live with paradox; beyond "either-or" to "both-and" thinking. Breathing in and breathing out illustrates the difference. Either-or thinking sees them as opposites. Both-and thinking sees them as needing each other. The more we can breathe in, the more we can breathe out. One such paradox is the advice process: it is a decision-making process that at once encourages individual initiative and the voice of the collective. It's both-and.

More to read

An Introduction to the Advice Process, with a video of Frédéric Laloux on this topic http://dev.alchemi.co.uk/adviceprocess/#/page/5cf823717fb0de42f3aeddfc

Frequently Asked Questions

Colleagues know that using the advice process isn't optional. One way to be dismissed is to ignore the mutual obligations of the advice process. With a conflict resolution process (as in some Teal entities) someone who feels the advice process is not being respected can hold a colleague to account.

But when people get used to it, respect for the practice grows. This because people are on both sides of the equation. When you ask me for my advice this morning, I hope you will take it seriously. If our roles are reversed this afternoon, I need to take you seriously, too. Because power is distributed, you know that others can take decisions about things you care about as well, so you are apt to take their needs and views into account.

Put another way: Who can decide who makes what decisions, while still using the advice process?

In practice, initiating advice and decision making usually fits within in the scope of a certain role. Someone sensing a problem or an opportunity could step forward to say: "Hey, I see this opportunity. What do you think? Given your role should you initiate this?". However, if that person doesn't have the interest or bandwidth to lead the process, any other person can. If no one does, it usually means the decision is not that important right now.

Holacracy adds a twist: for particularly sensitive areas, a "domain" can be declared. A domain basically means "hands-off". Decisions relating to that domain can only be made by nominated person(s). The idea is that domains remain exceptional and shouldn't be used frequently.

Sensing as a natural outcome of self-management

The simplest answer is often: Do nothing special. Let self-management work its magic. One word often comes up with Teal pioneers: Sensing. We notice when something isn’t working as it should, or could. With experience, our capacity to sense grows.

The Empty Chair

One practice to keep purpose foremost is to allocate an empty chair at meetings to represent our evolutionary purpose. Anybody can occupy the seat and represent the voice of the organization. Different questions can arise from this perspective: Have today's discussions and decisions served you (the organization) well? What stands out to you from today’s meeting? Are we being bold enough? Too bold? Is there anything else that needs to be discussed?

Large Group Processes

When facing a major inflection, some more elaborate processes help. These include Otto Scharmer’s “Theory U”, David Cooperrider’s “Appreciative Inquiry", Marvin Weisbord and Sandra Janoff’s “Future Search", Harrison Owen’s “Open Space Technology, Art of Hosting, World Café, etc. ”

In crises, time is of the essence. Is the advice process too unwieldy?

There are good examples of organizations that have used the advice process during crises. Rarely are decisions so urgent that a few hours can't be found to seek advice. And if possible, a crisis makes it even more important that a 'right' decision is made.

If, for some reason, the process does need to be suspended, two guidelines maintain trust in self-management: Full transparency about the scope and time frame of the crisis response, and making sure such powers clearly cease when the crisis is over.

In fact in many ways, the advice process allows for even faster and more decisive action, because many people in the organization practice being empowered decision-makers on a regular basis. In a well-functioning Teal organization, someone who is aware of a crises will weigh the advice it's feasible to get in the time they have, and make a judgement call.

When decisions affect the whole organization, it is particularly important to make the right decision. Yet, in very large organizations, the decision maker can hardly meet with everyone.

Some use internal social networks, or decision-making tools like Loomio, for wide and swift consultation. The initiator puts the proposal up as a post. Colleagues offer advice by responding on-line. If their comments signal agreement, the decision can be made very quickly. If new perspectives and debate emerge, the decision maker can choose to amend his proposal and float it again. If it appears decision time is not yet ripe, a working group may be set up.

Predictions offer a comforting sense of control, but reality is that organizations and the world they exist in are complex. In such systems, it is meaningless to predict the future with great confidence.

Teal Organizations accept a complex world in which perfection is elusive. They don't aim for perfection, but for workable solutions that arise from current reality, and which can be implemented quickly.

If there is a workable solution on the table (“workable” = the solution won't make things worse), it will be adopted. Decisions are not postponed because someone thinks more analysis will produce a better decision. The decision can be reviewed at any time. This is the essence of a culture of continuous iterative improvement.

Brian Robertson from Holacracy uses a powerful metaphor to contrast the two approaches:

“Imagine if we rode a bicycle like we try to manage our companies today. It would look something like this: we’d have our big committee meeting, where we all plan how to best steer the bicycle. We’d fearfully look at the road up ahead, trying to predict exactly where the bicycle is going to be when. … We’d make our plans, we’d have our project managers, we’d have our Gantt charts, we’d put in place our controls to make sure this all goes according to plan. Then we get on the bicycle, we close our eyes, we hold the handle bar rigidly at the angle we calculated up front and we try to steer according to plan. And if the bicycle falls over somewhere along the way ... well, first: who is to blame? Let’s find them, fire them, get them out of here. And then: we know what to do differently next time. We obviously missed something. We need more upfront prediction. We need more controls to make sure things go according to plan.”

In the Teal paradigm, the rider gets on the bike, starts with an angle that seems about right, and then keeps adjusting to get to the destination. Companies working this way often progress faster, and more smoothly toward their purpose, with less wasted energy.

Among Teal management practices, multiple bottom line accounting systems are rare. There is a school of thought that suggests we need ways to track not just profit, but also the firm’s impact on people and planet. How else can managers make trade-offs between these elements?

Perhaps the answer lies elsewhere: Multiple bottom lines originated to avoid a narrow fixation on profits. From a Teal perspective, a wider perspective already exists. Purpose, integrity and wholeness should transcend the primacy of profits.

Concrete cases for inspiration

Enspiral is a distributed collective using a consent-based advice process emphasizing online communication, inclusion, and individual autonomy.

Enspiral is a network of highly autonomous individuals, teams, and ventures. As much as possible, we encourage people to make decisions for themselves. Enspiral is also a network building shared commons, and pursuing shared aspirations, that call for collective agreements and commitments. There are a variety of situations where it is useful or necessary to make a formal decision as a group. See details here.

Holacracy uses two types of decision making: "autocratic" and "integrative", both of which, on close scrutiny, can be seen as variations of the advice process.

Governance decisions (decisions about people's roles and accountabilities) are made using "Integrative decision making". All others are made "autocratically".

Integrative decisions making

When someone senses a role must be created, amended or discarded, he brings it up in a governance meeting. These are meetings where only questions about roles and collaboration are to be discussed. That is, separate from the details of getting work done. The latter are discussed in “tactical meetings”, with their own specific meeting practices.

A facilitator guides the proceedings.

Anybody who feels a role change is needed (the proposer) can add it to the agenda. Each governance item is resolved with to the following process:

- Present proposal: The proposer states his proposal and the issue this proposal is attempting to resolve.

- Clarifying questions: Anybody can seek information or more understanding. It is not yet time for reactions. The facilitator will interrupt any question that cloaks a reaction.

- Reaction round: Each person reacts to the proposal. Discussions are not allowed.

- Amend and clarify: The proposer can clarify his proposal further, or amend it, based on these reactions.

- Objection round: The facilitator asks, ”Do you see any reasons why adopting this proposal would cause harm or move us backwards?” Objections are captured without discussion; the proposal is adopted if none surface.

- Integration: If an objection is raised, the facilitator tests the objection for validity. If it is found to be valid, he leads a discussion to craft an amendment that would avoid the objection. If several objections are raised, they get addressed one at a time, until all are removed.

There are strict criteria for an objection to be considered valid. The process might sound formal, but people who use it often report they find it deeply liberating. It addresses issues without the need for corridor talk, politics, and coalition building. Anybody who senses the need for something to change has a forum.

Others are surprised at how efficient this process is.

Holacracy’s governance process is a variation of the advice process. Anyone can bring forward an issue or opportunity (a "tension" in holacratic language) and make a decision happen, after listening to relevant advice. The particularity of the process here is that the advice happens in the setting of a meeting, with a structured number of rounds, and that the decision maker must integrate valid objections, if there are any. The goal, again, is to not to aim for a perfect answer, but a workable solution, and then iterate quickly if needed.

Roles evolve organically, adapting to change in the environment.

Autocratic decision making

In Holacracy, any decision other than governance decisions can be made "autocratically". Only when a "domain" is declared, which should be in exceptional circumstances only, are decisions off-limits to others. In all other cases, anyone can step up and make any decision.

Decisions can be made "autocratically", meaning no one needs to be consulted, and there is no formal process such as in the integrative decision making process. Yet in practice, people are well advised to seek advice when relevant.

If person A makes an autocratic decision that frustrates person B who has an obvious stake in that decision, person B is likely to bring up the topic in the next governance meeting. For example, if person (A), whose role it is to book meeting venues, chooses a new venue without discussing it with the main trainer (B) who has ideas as to what kind of venue is necessary for that specific training. The trainer (B) will suggest to amend the role of person A so that person A must consult the trainer before making decisions on venues in the future. Ultimately it boils down to the same: either person A spontaneously and informally seeks advice from person B, or it is likely that the role person A is currently energizing will be changed so that this role must formally seek advice from the trainer role (person B) before deciding on a venue.

Morning Star uses the advice process. Here is an example: it was used when a new strategy was proposed that would affect all employees.

A few years ago, before the advent of internal social networks, Chris Rufer, the founder, owner and CEO of Morning Star, felt the need for a new strategic direction at Morning Star. He wrote a memo that he sent to all colleagues, with an invitation to a company-wide meeting (the different locations joined by videoconference). He shared his idea, and the reasons for it. He asked everyone to contact him personally after the meeting with any questions, concerns, comments, and advice on his plans.

Buurtzorg has found an effective way for making decisions that affect large numbers of people.

Buurtzorg uses social media (as mentioned above) in a powerful and way to support the advice process. For example, if all 9,000 employees must be consulted, Jos de Blok, the founder, posts his suggestions on-line. He posts regularly, from the heart, without PR polish (there is no communications department at Buurtzorg), often at 10pm at night from his home.

Given the respect he enjoys, his posts are widely read. Typically, 24 hours later, a majority of nurses will have read the post. Within hours, these posts evoke dozens, sometimes hundreds, of comments.

This can make for fast decision-making. If the comments signal agreement, it is made within hours. If debate ensues, the proposal is amended and floated again. Or a workgroup is set up to refine it.

This kind of leadership by blog post requires a degree of trust, candor and vulnerability that few CEOs in would feel comfortable with. Once a post is published, there is no going back. Critical comments and rebukes are for all to see; they cannot be erased and cannot be ignored. And what the organization does with the post is beyond the CEO’s control.

What seems risky when looked at through a traditional lens is wonderfully efficient from a Teal perspective. A post made from the comfort of a sofa at home can be a decision by next afternoon, endorsed by thousands of people in the organization. An idea or concern about where the industry is going? Write a short post, and you get to know how the organization reacts. If people disagree with your thought, you have lost 15 minutes of your time … but gained a new insight into what the organization thinks. When we think of how decision-making happens in large organizations today (the PowerPoint decks that need to be written, the lengthy steering committee and executive meetings where decisions get debated, followed by top-down communications where every word is weighted), we can only marvel at the efficiency of leadership and decision making within Buurtzorg.

Buurtzorg uses a formal when decisions are made within a team

Buurtzorg's employees work in 750+ teams of 10-12 people. These teams are largely autonomous. Many decisions (say how the night shifts are handled, if there is room to accept more clients, etc.) affect the whole team, but no one else. Then, it makes sense for the advice process to take place within a team meeting. Buurtzorg uses a specific method for decisions called “Solution-Driven Methods of Interaction" developed by Ben Wenting and Astrid Vermeer of the Instituut voor Samenwerkingsvraagstukken in the Netherlands.

The group chooses a facilitator for the meeting.

The agenda of topics is put together on the spot. The facilitator can only ask questions: “What is your proposal?” or “What is the rationale for your proposal?” All proposals are listed on a flipchart.

Topics are then addressed one by one. In the first round, proposals are reviewed, and refined.

In a second, proposals are put to group decision based on a consent (not consensus). For a solution to be adopted, it is enough that nobody has a principled objection. If there are none, the solution will be adopted, with the understanding that it can be revisited at any time when new information is available.

Decisions made by front line, CEO makes no decisions

From 1992, when Henry read Maverick, to 2017, Happy sought to give people trust and freedom and job ownership. However it could not be described as a self-managing organisation as many decisions were made by Henry and Cathy.

In 2017 a key change happened. Learning from David Marquet, Henry and Cathy decided to stop making decisions, and instead to push them down to front-line staff. The results were remarkable, with people stepping up and taking responsibility. The effect on sales were dramatic, see here.

Even before 2017 Happy had been practising the concept of pre-approval, the idea that you approve a solution - within clear guidelines - in advance. https://www.happy.co.uk/blogs/pre-approve-it/

The CEO role is not to make decisions but to set the framework and be sure the right metrics are being measured.

Example: There are two key metrics in training delivery: customer satisfaction and training utilization. Customer satisfaction delivers delighted customers, but for the company to be profitable trainer utilisation is key. “All our facilitators are focused on the feedback they will get. But they aren’t so focused on utilisation. So I asked them to, each month, measure their utilisation. We didn’t set targets or anything, we just asked folk to measure it. That step alone resulted in a £95k increase in profits.” “I get to do what I love to do and feel what I am best at, which is coming up with new products,” explains Henry. In April 2021 this has meant creating a “Happy MBA”.

Here an example of frontline decision-making : in 2018 Ben and John felt that the prices of their courses needed increasing. They used the Advice Process, asking others for their views but making the final decision themselves.

“I was consulted”, explained Henry. “But actually they chose to go much higher than I would have gone. But that's fine, that is the effect of taking real responsibility.”

Clear roles and responsibilities with the advice process

Each team has built out the roles and responsibilities of everyone in the group, so it’s clear who would be able to make decisions within the company on different subjects.

If a responsibility falls into an individual’s area, they’re able to direct change and improvement using the advice process.

This video provides more information on Reddico’s advice process, and how it works: https://www.loom.com/share/07ffe72b66d542c9bcbc08fea83556cf

Please note that even though it’s stated in the video “Strictly private and confidential”, it’s OK to share it :-)

At LIVEsciences, there are three types of decision making.

- Single decision making with advice

- Consent

- Consensus

Individual Decision Making with Advice

In this case, decision authority lies with the roles. Everyone is entitled to take any decision at any time – LIVEsciences team members trust each other to do the right thing no matter what. This is the most common decision at LIVEsciences and it typically involves only a few people. An example of an individual decision is deciding how to create a workshop. As a default rule, LIVEsciences uses single decision-making combined with the advice process, meaning that any person can take any decision after seeking advice from:

- All stakeholders who will be significantly affected or at least key representatives of these groups

- People with expertise in the matter or holding relevant information for this decision, e.g. the “Finance Manager” role for decisions with significant out-of-pocket cost involved

Advice received shall be taken into consideration. However, advice is simply advice. No colleague can advise the decision-maker what to decide. With all the advice and perspectives in mind, the decision-maker chooses what he/she believes is the best course of action. Usually, the decision-maker is the person who notices an issue first, he/she is the owner of a specific role or he/she is affected by the issue.

Decision Making by Consent

LIVEsciences is also leveraging consent decision making. Consent means the absence of objections and going with a “good enough for now, safe enough to try” solution. When there are any objections, i.e. significant risks to the survival of the company, the decision cannot be taken, and the objections need to be dealt with (e.g., by seeking understanding or revising content).

Decision Making By Consensus

LIVEsciences has two exceptions where they switch to decision making by consensus as these decisions have a higher criticality to their business. Typically very few decisions require consensus and the number of people involved is normally higher compared to the other decision types:

- Recruiting requires consensus within the panel of three colleagues

- Purpose changes require consensus across the company

Status of August 2022