Self-Management

This article discusses one of the three fundamental innovations or “breakthroughs” brought about by Teal organizations.

Une nouvelle perspective

Leading scientists believe that the principal science of the next century will be the study of complex, autocatalytic, self-organizing, non-linear, and adaptive systems. This is usually referred to as “complexity” or “chaos theory” (the Teal equivalent to Orange’s Newtonian science). But even though we are only now starting to get our heads around it, self-management is not a startling new invention by any means. It is the way life has operated in the world for billions of years, bringing forth creatures and ecosystems so magnificent and complex we can hardly comprehend them. Self-organization is the life force of the world, thriving on the edge of chaos with just enough order to funnel its energy, but not so much as to slow down adaptation and learning.[1]

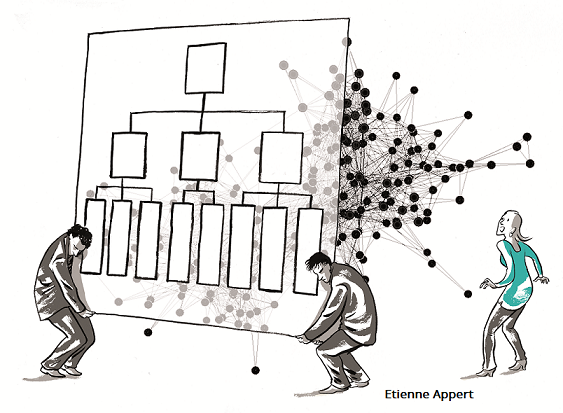

All stages of organizations prior to Teal have relied on a hierarchical power structure, with certain people exerting authority over others. The concentration of power and decision-making at the top, separating colleagues into the powerful and the powerless, brings with it problems that have plagued organizations for as long as we can remember. Power in organizations is seen as a scarce commodity worth fighting for. This situation invariably brings out the shadowy side of human nature: personal ambition, politics, mistrust, fear, and greed. At the bottom of organizations, it often evokes the twin brothers of powerlessness: resignation and resentment. The widespread lack of motivation we witness in many organizations is a devastating side effect of the unequal distribution of power. For a few lucky people, work is a place of joyful self-expression, a place of camaraderie with colleagues in pursuit of a meaningful purpose. For far too many, it is simply drudgery, a few hours of life “rented out” every day in exchange for a paycheck. The story of the global workforce is a sad tale of wasted talent and energy.[2] [3] [4]

Earlier stage organizations are seemingly built on the assumption that people cannot be trusted to act in the organization’s best interest without supervision. Teal Organizations are built on a foundation of mutual trust. Workers and employees are seen as reasonable people that want to do good work and can be trusted to do the right thing. With that premise, very few rules and control mechanisms are needed. And employees are energized to make extraordinary things happen.

En pratique

Self-management in Teal comes about through a combination of innovative structures and processes. These are described in detail throughout the wiki, but a few are highlighted below:

Autonomous teams

The most common structure of Teal organizations are interdependent networks of small, autonomous teams. The nature of these networks will take a variety of forms, depending on the characteristics of their industry and environment, but all consist primarily of teams, usually 10-20 people, that self-organize and are not under the authority of anyone outside the team.

No bosses or organization chart

There are no fixed hierarchies of authority in Teal organizations. There are no bosses within or outside of the teams. The primacy of the boss-subordinate relationship is replaced with peer-based mutual commitments. Decision rights and power flow to any individual who has the expertise, interest, or willingness to step in and contribute to a situation. Fluid, natural hierarchies replace the fixed power hierarchies of the traditional pyramid - leaving the organization without an organizational chart. See also Organizational Structure.

No job descriptions or job titles

There are typically no job descriptions or job titles in Teal organizations. Rather each individual has a number of roles that he/she has agreed to and committed to fulfill. When someone senses an issue or an opportunity that calls for a new role, someone simply steps forward and offers to take on that role. See also Job Titles and Job Descriptions and Role Definition and Allocation.

Distributed decision-making

Decision-making is highly distributed. Decisions do not need to be validated by the hierarchy nor by consensus of the community. Any person can make any decision after seeking advice from 1) everyone who will be meaningfully affected, and 2) people with expertise in the matter. See also Decision Making.

Open Information flow

Everybody is given access to all information at the same time. See also Information Flow.

Conflict resolution

Disagreements are resolved among peers using a well defined conflict resolution process. Peers hold each other accountable for their mutual commitments. See also Conflict Resolution.

Foire Aux Questions

A 2009 Ernst & Young study found that Buurtzorg (see “Concrete examples for inspiration” below) requires, on average, close to 40 percent fewer hours of care per client than other nursing organizations— which is ironic when you consider that nurses in Buurtzorg take time for coffee and talk with the patients, their families, and neighbors, while other nursing organizations have come to time “products” in minutes. Patients stay in care only half as long,heal faster, and become more autonomous. A third of emergency hospital admissions are avoided, and when a patient does need to be admitted to the hospital, the average stay is shorter. The savings for the Dutch social security system are considerable— Ernst & Young estimates that close to € 2 billion would be saved in the Netherlands every year if all home care organizations achieved Buurtzorg’s results. Scaled to the US population, this savings would be equivalent to roughly $ 49 billion[5]

In the case of FAVI (see “Concrete examples for inspiration” below), a foundry based in France, all its competitors have moved to China to enjoy cheaper labor costs. And yet FAVI is not only the one producer left standing in Europe; it also commands a 50 percent market share for its gearbox forks. Its product quality is legendary, and its on-time delivery close to mythical: workers are proud of their record of not a single order delivered late in over 25 years. FAVI delivers high profit margins, year in and year out, despite Chinese competition, salaries well above average, and highly cyclical demand patterns.[6]

Pluralistic-Green organizations seek to deal with the problem of power inequality through empowerment, pushing decisions down the pyramid, and they often achieve much higher employee engagement. But empowerment within the traditional hierarchy means that someone at the top must be wise or noble enough to give away some of his power, and those below are subject to that power being reclaimed.[7]

In Teal Organizations: the point is not to make everyone equal; it is to allow all employees to grow into the strongest, healthiest version of themselves. Gone is the dominator hierarchy (the structure where bosses hold power over their subordinates). And precisely for that reason, lots of natural, evolving, overlapping hierarchies can emerge— hierarchies of development, skill, talent, expertise, and recognition, for example. This is a point that management author Gary Hamel noted about Morning Star:[8]

Morning Star is a collection of naturally dynamic hierarchies. There isn’t one formal hierarchy; there are many informal ones. On any issue some colleagues will have a bigger say than others will, depending on their expertise and willingness to help. These are hierarchies of influence, not position, and they’re built from the bottom up. At Morning Star one accumulates authority by demonstrating expertise, helping peers, and adding value. Stop doing those things, and your influence wanes— as will your pay.[9]

Cas concrets d'organisations

A global, engineering company run largely without hierarchy or central control

Sun Hydraulics is a global producer of hydraulic cartridge valves and manifolds with hundreds of engineering projects running in parallel. Despite this, there is no master plan. There are no project charters and no one bothers with staffing people on projects. Project teams form organically and disband again when work is done. Nobody knows if projects are on time or on budget, because for 90 percent of the projects, no one cares to put a timeline on paper or to establish a budget. A huge amount of time is freed by dropping all the formalities of project planning - writing the plan, getting approval, reporting on progress, explaining variations, rescheduling, and re-estimating, not to mention the politics that go into securing resources for one's project or to find someone to blame when projects are over time or over budget. According to one of Sun's leaders, "We don't waste time being busy".[10]

A vast organization run almost entirely with small, independent teams

Within Buurtzorg (which means “neighborhood care” in Dutch), nurses work in teams of 10 to 12, with each team serving around 50 patients in a small, well-defined neighborhood. The team is in charge of all the tasks that were previously fragmented across different departments. They are responsible not only for providing care, but for deciding how many and which patients to serve. They do the intake, the planning, the vacation and holiday scheduling, and the administration. They decide where to rent an office and how to decorate it. They determine how best to integrate with the local community, which doctors and pharmacies to reach out to, and how to best work with local hospitals. They decide when they meet and how they will distribute tasks among themselves, and they make up their individual and team training plans. They decide if they need to expand the team or split it in two if there are more patients than they can keep up with, and they monitor their own performance and decide on corrective action if productivity drops. There is no leader within the team; important decisions are made collectively.[11]

A competitive global supplier run without middle management

FAVI’s factory has more than 500 employees that are organized in 21 teams called “mini-factories” of 15 to 35 people. Most of the teams are dedicated to a specific customer or customer type (the Volkswagen team, the Audi team, the Volvo team, the water meter team, and so forth). There are a few upstream production teams (the foundry team, the mold repair team, maintenance), and support teams (engineering, quality, lab, administration, and sales support). Each team self-organizes; there is no middle management, and there are virtually no rules or procedures other than those that the teams decide upon themselves.[12]

Notes et references

Laloux, Frederic (2014-02-09). Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness (Kindle Locations 2997-3003). Nelson Parker. Kindle Edition. ↩︎

Laloux, Frederic (2014-02-09). Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness (Kindle Locations 1416-1423). Nelson Parker. Kindle Edition. ↩︎

A 2012 survey conducted by Tower Watson, a human resources consulting firm polled 32,000 workers in the corporate sector in 29 countries to measure employee engagement (as well as the key factors contributing to engagement, such as confidence in senior management and the perceived interest by senior management in employee well-being). The overarching conclusion: just around a third of people are engaged in their work (35 percent). Many more people are “detached” or actively “disengaged” (43 percent). The remaining 22 percent feel “unsupported.” ↩︎

For a deep discussion of what motivates the modern worker, see Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us by Daniel Pink, Riverhead Hardcover, 2009. ↩︎

Laloux, Frederic (2014-02-09). Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness (Kindle Locations 1521-1527). Nelson Parker. Kindle Edition. ↩︎

Laloux, Frederic (2014-02-09). Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness (Kindle Locations 1690-1694). Nelson Parker. Kindle Edition. ↩︎

Laloux, Frederic (2014-02-09). Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness (Kindle Locations 1431-1433). Nelson Parker. Kindle Edition. ↩︎

Laloux, Frederic (2014-02-09). Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness (Kindle Locations 3050-3058). Nelson Parker. Kindle Edition. ↩︎

Gary Hamel, “First, Let’s Fire All the Managers,” Harvard Business Review, December 2011, http:// hbr.org/ 2011/ 12/ first-lets-fire-all-the-managers, accessed April 11, 2012. ↩︎

Laloux, Frederic (2014-02-09). Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness (Kindle Location 1927). Nelson Parker. Kindle Edition. ↩︎

Laloux, Frederic (2014-02-09). Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness (Kindle Locations 1498-1505). Nelson Parker. Kindle Edition. ↩︎

Laloux, Frederic (2014-02-09). Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness (Kindle Locations 1704-1708). Nelson Parker. Kindle Edition. ↩︎