Developmental Perspective on Organizations

This article discusses developmental models and their application to organizations.

A brief history of developmental models

A great number of scholars and thinkers―historians, anthropologists, philosophers, mystics, psychologists, and neuroscientists―have delved into the question: how has humanity evolved from the earliest forms of human consciousness to the complex consciousness of modern times? Some inquired into a related question: how do we human beings evolve today from the comparatively simple form of consciousness we have at birth to the full extent of adult maturity?

People have looked at these questions from every possible angle. Abraham Maslow looked at how human needs evolve along the human journey, from basic physiological needs to self-actualization. Others looked at development through the lenses of worldviews (Gebser, among others), cognitive capacities (Piaget), values (Graves), moral development (Kohlberg, Gilligan), self-identity (Loevinger), spirituality (Fowler), leadership (Cook-Greuter, Kegan, Torbert), and so on.

In their exploration, they found consistently that humanity and human beings evolve in stages. They do not evolve in the way that trees grow, continuously, but rather by sudden transformations, like a caterpillar that becomes a butterfly, or a tadpole a frog.

Our knowledge about the stages of human development is now extremely robust. Two thinkers in particular―Ken Wilber[1] and Jenny Wade[2]―have done substantial work comparing and contrasting all the major stage models and have discovered strong convergence. Each model might look at a particular side of the mountain (one looks at needs, another at cognition, for instance), but it seems to be the same mountain. While they often choose different names to refer to the stages or sometimes subdivide or regroup stages differently, the underlying phenomenon is the same - just like Fahrenheit and Celsius recognize, with different labels, that there is a point at which water freezes and another where it boils. This developmental view has been backed up by solid evidence from large pools of data; academics like Jane Loevinger, Susanne Cook-Greuter, Bill Torbert, and Robert Kegan have tested this stage theory with thousands and thousands of people in several cultures, in organizational and corporate settings, among others.[3]

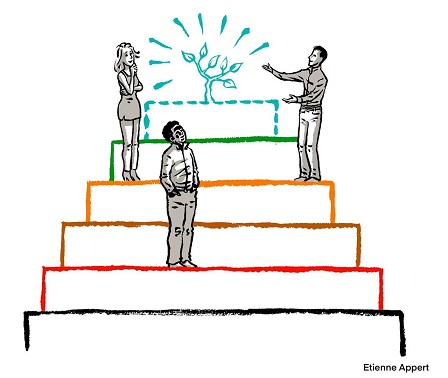

Every transition to a new stage of consciousness has ushered in a new era in human history. At each juncture, everything changed: society (going from family bands to tribes to empires to nation states); the economy (from foraging to horticulture, agriculture, and industrialization); the power structures; the role of religion. One aspect hasn’t yet received much attention: with every new stage in human consciousness also came a breakthrough in our ability to collaborate, bringing about a new organizational model. Organizations as we know them today are simply the expression of our current worldview, our current stage of development. Every time that we, as a species, have changed the way we think about the world, we have come up with more powerful types of organizations.[4]

This wiki is based largely on the work of Frederic Laloux in Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness. In his work, Laloux attempts to catalog the stages through which human organizational development has progressed. He portrays these stages in a way that borrows from many researchers, including those mentioned above, but particularly from the meta-analyses of Ken Wilber and Jenny Wade. As in Wilber’s Integral Theory, Laloux’s work and this wiki give colors as names to each stage of development. It should be noted that while the descriptions of stages here are generally compatible with Integral Theory, they may not always correspond exactly.

Some caveats

Experience shows that some people react in two extreme ways when confronted with this developmental theory.

- Some are so fascinated with these insights that they tend to apply them haphazardly, oversimplifying reality to fit the model.

- Others have the opposite reaction; they feel so uncomfortable with a model that could be used to label people and put them into different boxes that they reject the notion there is a developmental aspect to human evolution. They see the notion of such stages as elitist and implying that certain people are somehow better than others.

One stage is not necessarily "better" than the other

First, there is no wishing away the massive evidence that backs the view that human consciousness evolves in stages. The problem is not with the reality of the stages; it is with how we view the staircase. We get into trouble when we believe that later stages are “better” than earlier stages; a more helpful interpretation is that they are “more complex” ways of dealing with the world. For instance, a person operating from Pluralistic-Green can integrate people’s conflicting perspectives in a way that a person operating from Impulsive-Red most likely cannot. At the same time, every level has its own light and shadow, its own healthy and unhealthy expressions. Orange modernity, for instance, for all the life-enhancing advancements it has brought, has changed the planet in a way previous stages never could.

Another way to avoid attaching judgment to stages is to recognize that each stage is well adapted to certain contexts. If we were caught in a civil war with thugs attacking our house, Impulsive-Red would be the most appropriate paradigm to think and act from to defend ourselves. On the other hand, in peaceful times in post-industrial societies, Red is not as functional as some of the later stages.[5]

The map is not the territory

Second, any developmental theory is only an abstraction of reality, just like a geographical map is only a simplified depiction of a territory; it gives us distinctions that facilitate understanding of a complex underlying reality, but it cannot claim to offer a full portrayal of reality. The key is to hold these models as useful orientations that can help us get a richer appreciation of the extraordinary complexity of life.

Research shows that people (or even whole societies) do not operate neatly from just one paradigm. Humans are wonderfully complex and cannot be reduced to a single stage:

- Every stage includes and transcends the previous. So if we have learned to operate from, say, Achievement-Orange, we still have the ability, when appropriate, to react from Conformist-Amber or Impulsive-Red. Even the opposite is true to some extent: were we to be surrounded by people operating from a later stage, for example, Pluralistic-Green, we could temporarily display Green behaviors, even though we wouldn’t yet have integrated this stage.

- There are many dimensions of human development— cognitive, moral, psychological, social, spiritual, and so on— and we don’t necessarily grow at the same pace in all of them. For example, we might have internalized Orange cognition and be running an innovative business, but on the spiritual side, we espouse an Amber Christian fundamentalist belief.[6]

Similarly, one must apply development theory carefully with organizations. Few, if any, organizations fall neatly into just one stage. But if we look at an organization’s structure, its practices, and its cultural elements, we can generally discern what worldview they stem from. Let’s take the topic of compensation to illustrate this:

- If the boss can freely, on a whim, decide to increase or reduce pay, that would be consistent with the Red paradigm.

- If salaries are fixed and determined by the person’s level in the hierarchy (or the person’s diploma), that sounds in line with an Amber perspective.

- A system that stresses individual incentives if people reach predetermined targets probably stems from an Orange worldview.

- A focus on team bonuses would be in line with a Green perspective.

When one looks through this filter not only at compensation, but at all the structure, practices, and culture of an organization, one generally finds that they are not scattered randomly among the stages and colors, but cluster around a center of gravity, a stage that defines most practices of the organization.

The role of leadership

What determines which stage an organization operates from? To date, the answer has been - the stage through which its leadership tends to look at the world . Consciously or unconsciously, leaders put in place organizational structures, practices, and cultures that make sense to them, that correspond to their way of dealing with the world.

This means that organizations to date have not been able to evolve beyond its leadership’s stage of development. The practice of defining a set of shared values and a mission statement provides a good illustration. Because this practice is in good currency, leaders in Orange Organizations increasingly feel obliged to have a task force come up with some values and a mission statement. But looking to values and mission statements to inform decisions only makes sense as of the Green paradigm. In Orange, the yardstick for decisions is success: Let’s go with what will deliver top- or bottom-line results. In Orange organization’s, leadership might pay lip service to the values; but when the rubber hits the road and leaders have to choose between profits and values, they will predictably go for the former. They cannot uphold a practice and a culture (in this case, a values-driven culture) that stems from a later stage of development.

The pull of leaders toward their stage of consciousness goes in two directions: they can pull “back” practices from later stages (rendering them ineffective as in the previous example), but they can also exert a strong pull “forward.” The structure, practices, and culture they put in place can help employees adopt behaviors of more complex paradigms that they as individuals have not yet fully integrated.

Suppose I am a middle manager looking at the world mostly from a Amber perspective. My natural style with my subordinates would be to interact in very hierarchical ways, telling them exactly what they need to do and how they need to do it. Now let’s say I work in a Green Organization, where my leaders urge me to empower employees that work for me. All around me I see other managers giving their subordinates lots of leeway. Twice a year, I receive 360-degree feedback, including from my direct reports, telling me how well I’m doing on empowerment (which can affect my bonus); every six months, I’m asked to sit down with my team and discuss how well we are doing in living company values (which include empowerment). Within such a strong context of Green culture and practices, I’m likely to espouse some Green management skills and behaviors. The context has pulled me up, leading me to operate in more complex ways than I would if left to my own devices. And just perhaps, over time, when I’m ready for it, the context will help me grow and genuinely integrate into that paradigm.[7]

Having said this, it is important to note the concept of “leadership” is different in Teal. While earlier stages of organizational development relied fundamentally on a hierarchical power structure, with someone clearly “in charge”, Teal rejects the notion of a fixed hierarchy. The Teal organization is self-organizing and self-managing.

Ironically, at the foundation of a Teal organization there is commonly a strong leader who, sensing the potential, initiates the sharing of power: Jean-Francois Zobrist at FAVI, Chris Rufer at Morning Star, and Jos de Blok at Buurtzorg are good examples.

They imagined a different kind of organization, and a different kind of leadership: a leadership that is distributed, emergent and unpredictable. Anyone can lead—subject to an advice process—based on opportunity, circumstance and/or imagination.

One might argue that the reason “leaders” have played such an important role in Teal organizations to date is because these organizations (and we as a civilization) are making a transition from earlier stages reliant on the traditional type of leader. Perhaps in the not too distant future, Teal organizations will fully and truly emerge without assistance from a single or small group of enlightened individuals.

Notes et references

For an easy introduction: Wilber, Ken. A brief history of everything. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1996. For a more complete overview: Wilber, Ken. Integral Psychology. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2000. ↩︎

Wade, Jenny. Changes of Mind: A Holonomic Theory of the Evolution of Consciousness. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996. ↩︎

Laloux, Frederic (2014-02-09). Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness (Kindle Location 493-501). Nelson Parker. Kindle Edition. ↩︎

Laloux, Frederic (2014-02-09). Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness (Kindle Locations 476-506). Nelson Parker. Kindle Edition. ↩︎

Laloux, Frederic (2014-02-09). Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness (Kindle Locations 996-1004). Nelson Parker. Kindle Edition. ↩︎

Laloux, Frederic (2014-02-09). Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness (Kindle Location 1009-1016). Nelson Parker. Kindle Edition. ↩︎

Laloux, Frederic (2014-02-09). Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness (Kindle Location 1068-1076). Nelson Parker. Kindle Edition. ↩︎